Where Culture and Ecology Meet to Create Paradise

For thousands of generations human societies have interacted with nature. We know this because all cultures have rules to protect or preserve natural places as sacred sites, national parks or reserves and community conservation areas. In our generation conservation is still very important but most initiatives tend to focus on biological diversity primarily, perceiving cultural diversity as a secondary objective or a stepping stone to protecting biodiversity. A great deal still needs to be accomplished in order to shift our paradigms and transform the way people think about global diversity, whereby biological and cultural diversity are thought of as one.

There has been some headway made in reshaping the way in which protected areas are conceived. There is increasing recognition of the importance of Community Conserved Areas. These are places managed by local communities in ways that support high levels of biodiversity, but which often have no official “protected” status. The Kaya forests of the Mijikenda are worthy of mention as a cultural and biological landscape that is beginning to receive the official recognition and protection they deserve. It is a great example of where the interaction of humans and nature over time has produced a particular set of natural and cultural conditions. It is also interesting to note how in this case culturally defined taboos may play an increasingly important role for biodiversity conservation on a local and regional level. Mijikenda tradition made it taboo for the Kayas to be desecrated thus designating the Kayas as sacred groves. Under current rates of deforestation and species loss, sacred groves worldwide are becoming crucial ecologically as a potential buffer against the depletion of genetically adapted local variants and overall biodiversity in a region. They can serve as important recruitment areas to surrounding ecosystems.

We are learning to appreciate diversity not as a distinct entity, but as an intertwining of natural and cultural elements encompassing biological diversity, human beliefs and values, worldviews and cosmologies, as opposed to viewing biological and cultural diversity as being separate from one another. The natural environment provides a framework for cultural processes, activities and belief systems to develop. This framework provides a feedback system where a shift in one system often results in a change in the other. Biological diversity reinforces the resilience of natural systems whilst cultural diversity enhances the resilience of social systems.

Mombasa County is a crucial example of how biological and cultural diversity rely on one another, and losing one or the other can create conditions for the gradual loss of both. Mombasa has many well known cultural heritage sites as well as natural heritage sites. Mombasa city the capital is a harbor city and serves as a major channel of trade between East and Central Africa and the rest of the world. The city and its surrounding areas also account for a large proportion of income from tourism for the country. But as in many parts of the country these resources are quickly disappearing because of social, economic and environmental pressures. The dynamics of society and the evolution of cultures have changed people’s value systems and hence their uses of and interaction with the environment. The competition between traditional and modern commercial resource extraction (e.g. artisanal fishing versus commercial fishing), and pivotal investments such as tourism and other forms of recreation, have negatively affected ecosystems and their productivity. Destructive resource extraction practices, as well as extreme weather events such as flooding and drought and their associated impacts on marine ecosystems also serve to diminish the productivity of the natural habitats that coastal communities have been depending on and protecting for their livelihoods thus also diminishing their illuminative significance.

Heritage includes the collective memory and oral histories which affirm the value of cultural assets through time. Where there is a decline in value of traditional knowledge systems and practices, and the replacement of those systems with weak management institutions we lose the sense of identity those places evoke as well as the sensitivity towards the nature of human interaction in those places. The depreciation of resources that provide cultural ecosystem services often also lessens their aesthetic appeal and other intrinsic values.

One man has taken the bull by the horns and worked hard to reverse this trend. This is the story of Ngomongo ecotourist village located in Mombasa. The village was established by Dr. Fredrick Gikandi from an abandoned limestone quarry. The 40-foot deep quarry is located 600 meters offshore and had been earmarked as the municipality’s refuse dump site. Its floor is only four feet above the sea and which means the dump would have contaminated the water table which lies only four feet below the quarry floor, and by extension the Indian Ocean coastal and marine ecosystem.

Dr. Gikandi rehabilitated the quarry by planting eighty different indigenous trees; such as the Neem tree (mwarobaini- believed to be able to cure 40 diseases hence the name mwarobaini), trees, coconut trees, mango trees, date palms, Mvuli ( also known as Rock-elm or Milicia excels and whose wood used to build boats, produce hardwood furniture as well as building materials. Its bark is used to manufacture yellow dye and its leaves are beneficial for farming in that they provide mulch and fix nitrogen in the soil), Muratina (also known as Sausage tree of Kigelia Africana, whose wood is used for carving sculptures, and its leaves are used for medicine and insecticides and whose fruit is used as a fermentation agent for local brew). He later also planted the easier to grow Casuarinas. Dr. Gikandi has personally invested some US$200,000 in his reclamation project, which is serving as a model for other urban and non-urban communities, which are affected by degraded lands. Initially Dr Gikandi bought tree seedlings from government forest stations, which he planted at the quarry. Later he established the quarry’s own small seed bank with the community around the quarry helping by providing the seeds to set up a tree nursery and planting the trees.

Two natural ponds were excavated to form wetlands and a bird sanctuary with over fifty bird species. He mounted an awareness campaign to educate the public and when the area was completely reforested, he invited ten different tribesmen to replicate their rural homes in the small clearings of the new forest. The result of which is the now a well-known sustainable eco-cultural tourist village which provides cultural tourism to help with the sustainability of the tree planting work. The locals have also formed an NGO which has expanded the tree planting work to neighboring communities.

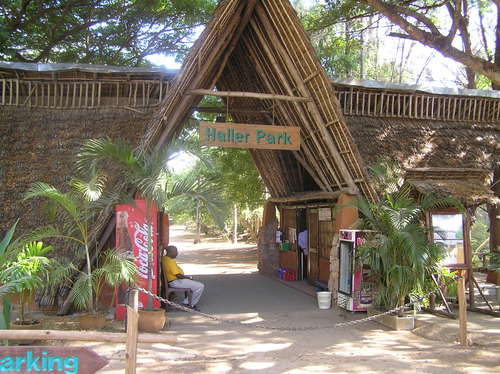

Another example is the rehabilitation of limestone quarries in what is today known as Haller Park. It is this project that was the inspiration for Dr. Gikandi’s project. It is the transformation of a quarry wasteland which belonged to Bamburi cement, into an ecological paradise. Before the creation of the nature park, the area was a cement quarry with 1.2 tons of cement being mined from the area annually. Quarrying resulted in a loss of cultivated land, loss of forest and pasture land, and the overall loss of production. The indirect effects included soil erosion, air and water pollution, toxicity, environmental disasters, loss of biodiversity, and ultimately loss of economic wealth. When the company decided to rehabilitate the area, Rene Haller, then head of Bamburi’s Garden & Agriculture Department spear headed the project.

Haller’s vision was to create a diverse, indigenous coastal forest. The aim was to re-vegetate the area with suitable tree species and other forms of flora and fauna in order to mitigate the impact of land degradation. The forest would become a refuge for trees and other plants, as well as for indigenous small wildlife, which were all threatened by population pressure and over-exploitation. By planting valuable, indigenous timber trees, medicinal and ornamental plants for sale, the forest became economically viable. A fish farm with salt-tolerant fishing ground water ponds was also established to pay for the long-term forestry development.

Even though the park was landscaped aesthetically from the beginning, the idea was not necessarily create a park open to the public .What they had not planned for was how the beauty of the area as well as the ingenuity of the man-made ecosystems, would attract visitors to the area creating more income as well as a heritage site for the city.

Both Ngomongo village and Haller Park demonstrate how the relationships between people and nature are socially and culturally conditioned, creating a diversity of reasons for conserving biodiversity across different cultures and societies. This diversity of interests and perspectives is key to resilience and the capacity to respond to change. Cultural approaches to biological conservation are essential not just to the design of conservation initiatives responding to changing circumstances, but to the staying power of communities and cultures themselves.